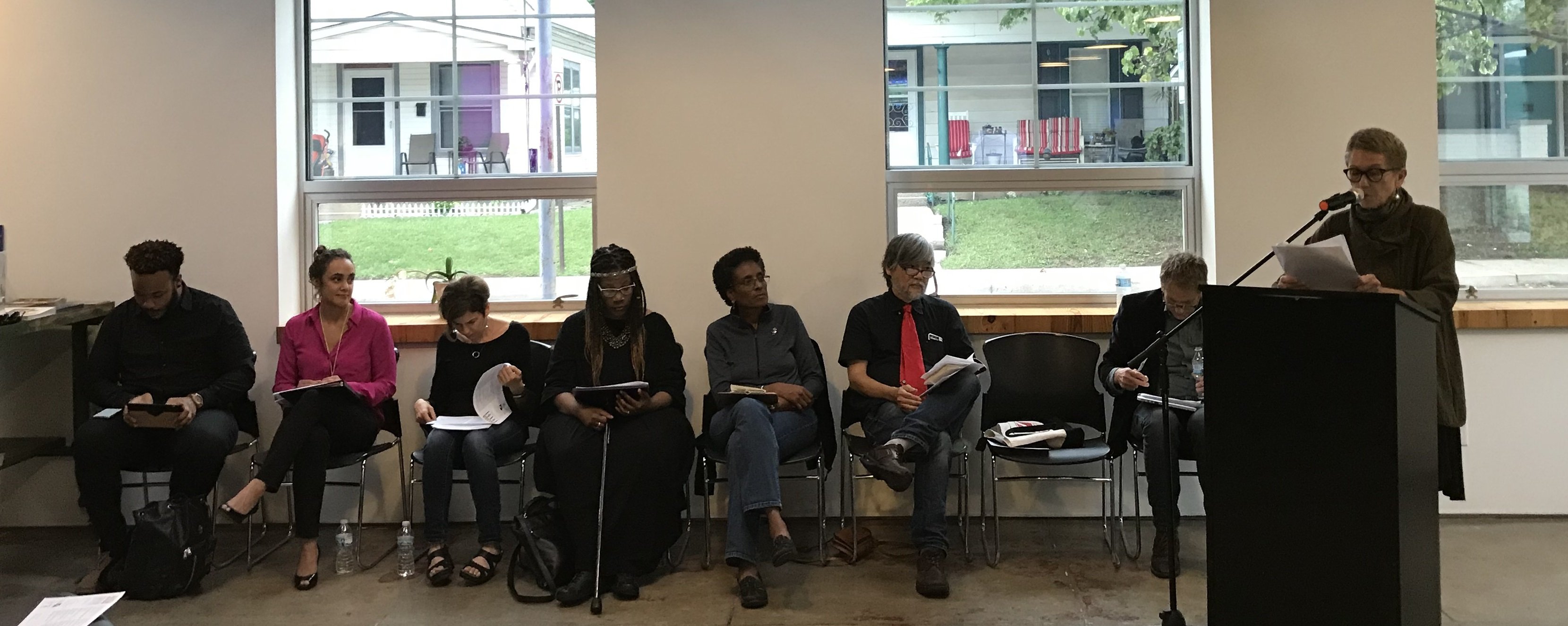

The Indiana Writers Center held “Breakout: Voices From the Inside” in partnership with PEN America on Monday, September 10, 2018 from 7-9 PM. Though the audience was small, all who attended, including the readers, agreed that they were moved by the presentation, which included work by PEN Prison Writing Contest winners, people incarcerated in the Indiana prison system, and Jeremy Richard, who is incarcerated at the Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, LA. Poems by Indiana poet Etheridge Knight, as well as poems by Reginald Dwayne Betts, who made it out of prison and are an inspiration to all of us. The work was read without interruption, as a program gave biographical information about writers and readers.

The program was as follows:

“Cell Song” by Etheridge Knight

Read by JL Kato

“discovery after twenty years in prison” by Sean J. White

Second Place, Poetry, PEN America Prison Writing Contest, 2018

Read by Karen Kovacik

“My Mind” by Dave

Read by Debra Des Vignes

“Five Haiku Plus Two” by Geneva J. Philips

Honorable Mention, Poetry, PEN America Prison Writing Contest, 2018

Read by Devon Ginn

“This Poem” by Etheridge Knight

Read by Celeste Williams

An excerpt from the writing of Jeremy Richard

Read by Barbara Shoup

“Going Forward with Gus” by Sterling Cunio

Second Place, Essay, PEN America Prison Writing Contest, 2018

Read by Michael McColly

“Break Free” by Brandon

Read by Debra Des Vignes

“Fragment of a Dream” by Gary K. Farlow

Honorable Mention, Poetry, PEN America Prison Writing Contest, 2018

Read by JL Kato

“The Idea of Ancestry” by Etheridge Knight

Read by Angela Jackson Brown

“The Storm” by Edward Ji

Honorable Mention, Poetry, PEN America Prison Writing Contest, 2018

Read by Celeste Williams

“Remembrance” by Foosie

Read by Debra Des Vignes

“Grace Notes” by Matthew Mendoza

First Place, Poetry, PEN America Prison Writing Contest, 2018

Read by JL Kato

An excerpt from the writing of Jeremy Richard

Read by Barbara Shoup

“At a VA Hospital” by Etheridge Knight

Read by Devon Ginn

“Only Human” by Daniel

Read by Debra DesVignes

“Regret’s Tragic Romance” by Annmarie Harris-Romero

Honorable Mention, Nonfiction PEN America Prison Writing Contest, 2018

Read by Angela Jackson Brown

“The Glitter Squirrel in Me” by Elizabeth Hawes

Third Place, Poetry, PEN America Prison Writing Contest, 2018

Read by Rachel Sahaidachny

“Dimensions” by Albert

Read by Debra Des Vignes

“The Swallow War” by St. James Harris Wood

First Place, Essay, PEN America Prison Writing Contest, 2018

Read by Michael McColly

“Ode to a Kite” by Reginald Dwayne Betts

Read by Karen Kovacik

Read an excerpt of “The Swallow War” by St. James Harris Wood

After fifteen years down, I assume that prison life can’t get any more off-kilter or annoying; but then, some cruel functionary starts a war against the local swallows. Each early dawn and during the fading light of dusk I love to watch the hardy little birds hurtling in tandem by the hundreds, coasting and whipping around the sky, exercising or herding bugs maybe, or perhaps just flying for the joy of it. I enjoy it, watching their huge swarm, a thousand strong, wheeling around like drunken feathered acrobats, breathtaking and beautiful as they pursue and eradicate every bee, fly, mosquito, moth, and whatever else is in the air and smaller than the hungry little assassins. Watching the sparrows is better than tv or pinochle and has the distinct bouquet of freedom.

In the hills surrounding my home, the California Men’s Colony, dwell macabre flying spiders who contrive to get to the top of our absurdly high (50 yards) light towers. The ambitious spiders lay thousands of eggs up there, and when the babies hatch, windy days are a signal for them to make web kites, and all at once the entire spider congregation takes off, mostly to be killed and eaten by the swallows, thank God; but last year the flying baby spiders launched themselves while the sparrows were off somewhere else, having heard of special mud for their nests in another county. The spiders spread across the sky, the yard, all over the buildings and grass, landing on our clothes and hair for an hour, until finally the sparrows returned home. It was a scene, or more properly an outburst of nature (a tantrum?) to see a thousand swallows dodging about en masse, performing maneuvers, eradicating the remaining spiders, still aloft. The baby spiders take it stoically as a countless number of their comrades had made it to the ground before the massacre. Like everyone, I can’t help but wonder how the swallows manage to perform their complicated mass dance and aerial gyrations—spinning, swirling, churning, clouds of feathers and grace so unlike our clumsy human world—without ever crashing into each other and falling to the ground like Icarus, or me.

These American Cliff Swallows have been coming to San Luis Obispo for a thousand years, flying up from Goya, Argentina (if we are to believe them), and once here they frantically, industriously search out little globs of mud and build nests that resemble tiny brown desert igloos. The prison is smack dab in the middle of the little birds’ centuries old customary nesting grounds. Figuring that we’ve placed the prison here for their convenience, the swallows build their nests in the infrastructure of the steel girders—imagine a bridge built in a square with all the little caches, tiny lairs, and small dens that three stories of steel beams offer. This singular edifice sits in the center of the prison; it’s open air and we call it the plaza. There are a couple of trees, some sickly grass, and a 100 yard circular sidewalk in the plaza connecting our four yards. All the cops, free staff, and convicts (around 3,000 people) march through it to work, to school, to the library, and everywhere else we are compelled to go during the day, from four in the morning until around ten at night. Right above the sidewalk is the metal structure with its niches, nooks, and crannies—about every four-five inches—where the swallows build their nests, and there are a couple thousand of these spaces in the plaza. It is a wonderfully odd and happenstance open air aviary—except of course for the barbed wire and incarceration. The swallows are free and the humans are trapped. As we walk back and forth beneath their nests to school and work, the swallows, who apparently aren’t afraid of humans, stare grumpily at us, trespassing in their prison.

For nine years I’ve watched the whole process: birds arrive, build nests like tiny lunatic construction crews, at dawn and dusk they twirl and swirl through the sky (often feinting and mock fighting for obscure reasons), and conveniently patrol our little valley and eat countless bugs. Out here in the near wilderness there are bugs galore and I am grateful that the mosquitoes, midges, and spiders are dealt such a blow, the swallows keeping them from my flesh. They have to maintain their high pitched metabolisms, fuel up for all the precise turbulent aerial displays, and when the time comes, feed their fledglings. Eggs are laid and the mock fighting increases as they defend their nests from imaginary threats. Soon (two weeks), frighteningly tiny swallows are hatched, mindlessly cheeping for bugs and whatever else is on the menu.

A bit more info about the program and those involved in Nuvo, “Indiana Writers Center Highlights Prison Writing.”

Presented by Indiana Writers Center in partnership with PEN America